Asian Community Sites & Forums: Where They Went & What's Used Now

In 1991, the internet was launched to the public, changing the way we would connect forever. Asian Avenue, a platform connecting Chinese ethnic groups and the broader Asian diaspora, launched in 1997, just 6 years later. This was run by co-founders Benjamin Sun, Peter Chen, Grace Chang, and Michael Montero.

A year later, the New York Times described it as “unusually successful.” At its peak, the site had 2 million users, with more than 5,000 online at a time. It became a hub for the American Born Chinese, Australian Born Chinese, British Born Chinese, and other Chinese people groups to speak out. In 1999, SKYY vodka displayed an advert of a Caucasian woman with chopsticks in her hair, and many users called out cultural appropriation.

What was particularly unique about Asian Avenue was that the user page was completely bespoke. Most young people, especially from the ESEA community, learnt HTML specifically to create their webpage. Moreover, there would be a profile of the week, where the users with the most views would feature on the homepage. Users would communicate through the guestbook, leading to new friendships and fostering community ties similar to those found in the London Chinese Community Centre.

The dynamic profile pages and excitement of user of the week created a buzz. Asian Avenue was a pioneer in connecting Asians online and became a virtual meeting space to discuss topics and cultural events in the UK and beyond. There is currently no information about why Asian Avenue disappeared.

The Rise of Community Forums

The early 2000s was an era of discussion forums. At a time when Dance Dance Revolution became popular, this led to the launch of the Dance Games forum. Although not strictly for Asians, many of the fans were from the community. They would arrange to meet at arcades and spend their weekends on the DDR machines, and afterwards go to bars and clubs. This became a regular routine, building a network of friends which would still stand the test of time.

British Born Chinese Discussion Forum vs. DragonLink

Then came the British Born Chinese Discussion Forum and DragonLink. Both were dedicated websites for the Asian community, with the former more focused on British Chinese, and the latter for all “Orientals in the UK”. This was before the term became derogatory. There was some stereotyping and healthy competition between the two. The British Born Chinese Discussion Forum was considered more mature and civilised, whereas DragonLink was considered more for younger party-going Asians.

Much of the community parties were promoted on these forums. Both would organise their own ‘Meets’, and ESEA club night organisers would advertise on the forums. DragonLink would advertise community news. There was a dedicated user profile page, where users could rate each other based on attractiveness. A girl with perfectly straightened hair in a red dress looking to the side would consistently feature over 9/10. On both forums, users would post in dedicated topic boards and were very active in keeping up with discussions.

Facebook’s Dominance and the Decline of Forums

Facebook launched in 2004 and became hugely popular. Discussions became stagnant on these forums as users connected with each other directly on Facebook. Users were more hooked on checking each other’s profile pages with personalised updates rather than discussing topics on a forum. As the engagement dwindled, the British Born Chinese discussion forum and DragonLink created pages in Facebook Groups. This saw a migration of discussions, leaving the original sites derelict.

Fragmentation in the 2020s

Fast forward to the 2020s and Facebook usage has decreased amongst all age groups, with only 1/3 of under 25s reportedly using the site. As Instagram rules supreme, this platform has fragmented the community connection experience. Today, the Asian diaspora follows some dedicated Asian community Instagram pages with event updates, but there is no central hub to promote these. Moreover, Instagram does not feature a community forum, so the community don’t have a space to discuss topics. The British Born Chinese group on Facebook boasts 16.5k users, but the user experience is somewhat less organised and tailored to the community.

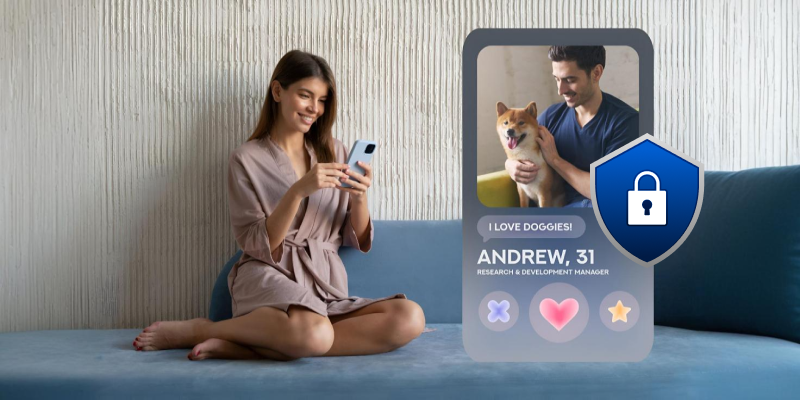

The Future: Maccha's Role in Reconnecting the Community

Maccha aims to bridge the gaps faced by the ESEA community and Asian diaspora in building connections, finding friends, and sharing real-life experiences. In a time when traditional hubs like the British-Born Chinese Forum and the London Chinese Community Centre have shifted focus, Maccha provides a modern digital platform where American-born Chinese, Australian-born Chinese, British-born Chinese, and all ESEA members can connect in one place. With dedicated spaces for discussion, discovering cultural events across the UK, and organised meetups, Maccha paves the way for a new chapter.